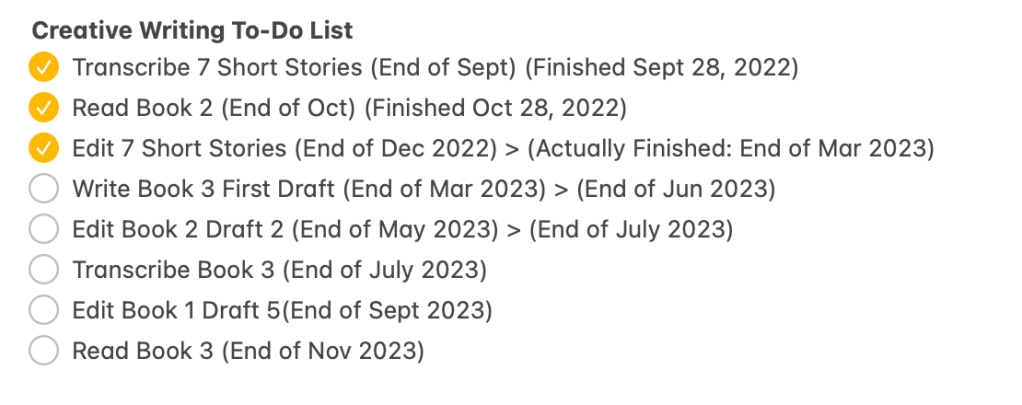

I’m currently working on a trilogy, and I’m well into the first draft of book 3.

I don’t usually outline my stories. And when I wrote the first drafts of book 1 and 2, as you may recall from these articles, I pants them… hard.

I see myself as a discovery writer. I have outlined in the past, but I don’t particularly like relying on it to write, because I find that it often creates restrictions in my workflow and I can’t be as fluid. I have to keep checking in on the outline to make sure I didn’t skip any key detail.

So why did I decide to outline this time?

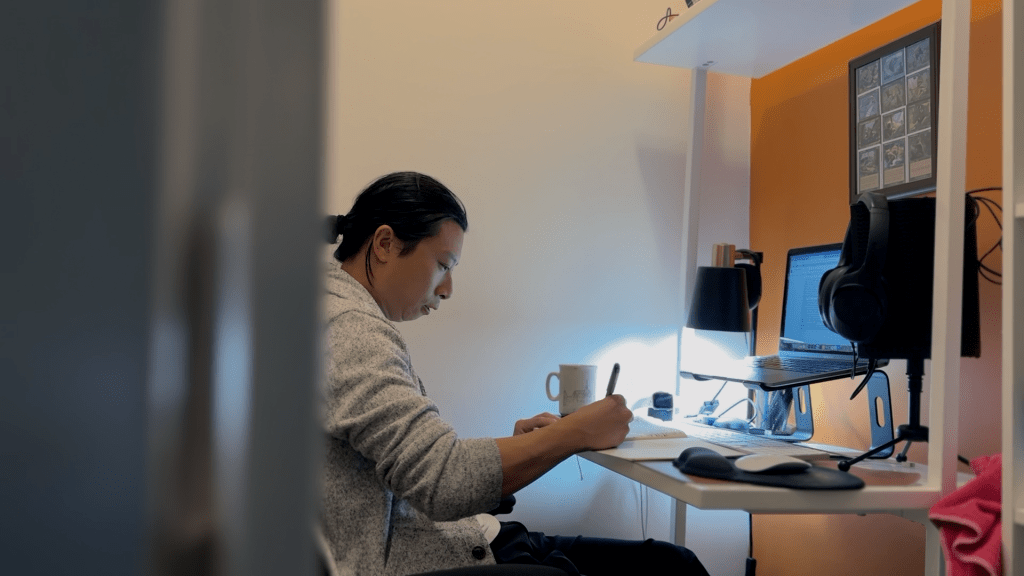

Honestly, I don’t have much time these days to work on my creative projects. And with only a short amount of time available each day—like 3 to 4 sessions a week—I didn’t want to wait for inspiration to strike. With an outline, I can see where I left off and get straight to work on creating scenes, figuring out what happens next, or writing dialogues.

At least, that was my plan. But outlines are hard to follow and all it takes is for me to make one change and like pulling out a Jenga piece from the bottom, the whole tower is shaky and if I make too many changes, the whole thing collapses, rendering the outline useless.

Right now, I’ve completed nearly half of the first draft, and what I’m noticing is that, yes, I’m making changes. The specifics about the characters and events are definitely shifting from the outline. However, I also have a clear idea of where the story should ultimately lead. So, even if I veer away from what I initially planned, it’s not a problem. I can take detours, explore new ideas, be creative, enjoy the process, and eventually return to the important story beats I need to include.

For instance, I need my character to return to his hometown to kick off the second part of the story and then participate in a big battle during the third part. I have a good sense of the crucial scenes that need to happen between those points, but the way I choose to write those scenes is where I have room to experiment without feeling restricted by the outline.

That’s precisely what the outline provides me with. If I were journeying across the globe, the outline would represent all the flights I must catch in between destinations. What I do once I touch down is subject to change, but eventually, I’ll need to return to the airport and catch my next flight. The outline serves as my travel itinerary, not the schedule for every day of the trip.

I’m not particularly fond of using outlines, but I do need to bring this project to a conclusion at some point. By having the outline, I’m aware of the destinations I must reach to ultimately wrap this up. Now, if you’ve been keeping up with my progress, you’d be aware that I’m taking my time with this endeavor. But even though I’m not in a rush, it doesn’t mean I lack the desire to finish. During a journey, there comes a moment when you feel an urge to leave the beach and embark on a different activity. That’s where the outline comes into play. It tells me that I’ve lingered here too long and it’s time to get going to the next scene.

This is how I keep myself from getting too frustrated when I deviate from my outline. I don’t discard it entirely; I still find value in using it. Its central elements are what I require. I’m free to modify scenes as much as I want, but I must hit those key plot points. The crucial thing is staying on track to hit those points. I’m in control. I can always guide my story back on course even if I stray off it.

That’s where I stand currently. I’m exploring as I work on the first draft of book three. I’m mostly enjoying this drafting process for the final time in this trilogy, because after this step, there’s going to be a lot of editing ahead. As much as I’m anticipating that phase, the first draft has always been the part I’ve enjoyed the most. This is another reason why the outline holds significance. It will push me beyond my comfort zone to see it through.

Join my YouTube community for insights on writing, the creative process, and the endurance needed to tackle big projects. Subscribe Now!

For more writing ideas and original stories, please sign up for my mailing list. You won’t receive emails from me often, but when you do, they’ll only include my proudest works.