Before we talk about Black Museum, let’s flashback to when this episode was first released: Dec 29, 2017.

In 2017, the rise of dark tourism—traveling to sites tied to death, tragedy, or the macabre—became a notable cultural trend, with locations like Mexico’s Island of the Dolls, abandoned abandoned hospitals and prisons drawing attention. Specifically, Chernobyl saw a dramatic increase in tourists, with around 70,000 visitors in 2017, a sharp rise from just 15,000 in 2010. This influx of visitors contributed approximately $7 million to Ukraine’s economy.

Meanwhile, in 2017, the EV revolution was picking up speed. Tesla, once a trailblazer now a company run by a power-hungry maniac, launched the more affordable Model 3.

2017 also marked a legal dispute between Hologram USA and Whitney Houston’s estate. The planned hologram tour, aimed at digitally resurrecting the iconic singer for live performances, led to legal battles over the hologram’s quality. Despite the challenges, the project was eventually revived, premiering as An Evening with Whitney: The Whitney Houston Hologram Tour in 2020.

At the same time, Chicago’s use of AI and surveillance technologies, specifically through the Strategic Subject List (SSL) predictive policing program, sparked widespread controversy. The program used historical crime data to predict violent crimes and identify high-risk individuals, but it raised significant concerns about racial bias and privacy.

And that brings us to this episode of Black Mirror, Episode 6 of Season 4: Black Museum. Inspired by Penn Jillette’s story The Pain Addict, which grew out of the magician’s own experience in a Spanish welfare hospital, the episode delves into a twisted reality where technology allows doctors to feel their patients’ pain.

Set in a disturbing museum, this episode confronts us with pressing questions: When does the pursuit of knowledge become an addiction to suffering? What happens when we blur the line between human dignity and the technological advancements meant to heal? And what price do we pay when we try to bring people back from the dead?

In this video, we’ll explore the themes of Black Museum and examine whether these events have happened in the real world—and if not, whether or not it is plausible. Let’s go!

Pain for Pleasure

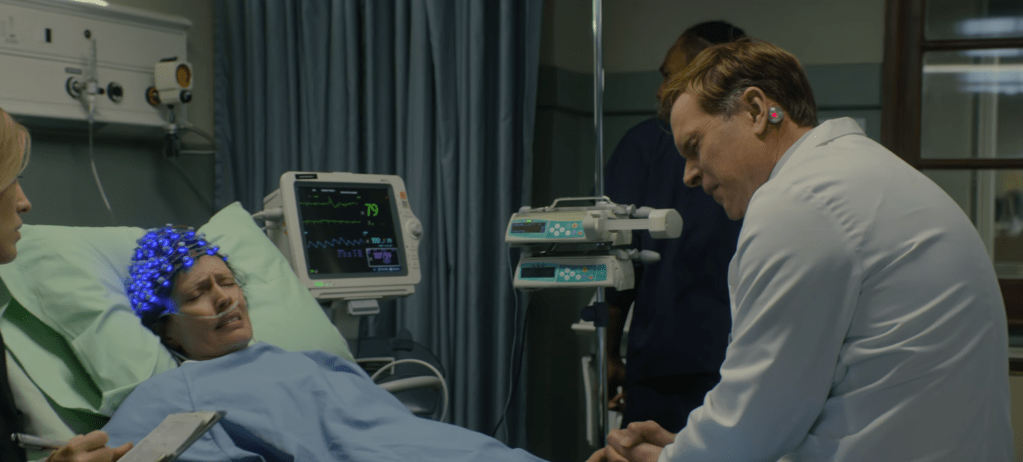

As Rolo Haynes guides Nish through the exhibits in the Black Museum, he begins with the story of Dr. Peter Dawson. Dawson, a physician, tested a neural implant designed to let him feel his patients’ pain, helping him understand their symptoms and provide a diagnosis. What started as a medical breakthrough quickly spiraled into an addiction.

Meanwhile, in the real world, scientists have been making their own leaps into the mysteries of the brain. In 2013, University of Washington researchers successfully connected the brains of two rats using implanted electrodes. One rat performed a task while its neural activity was recorded and transmitted to the second rat, influencing its behavior. Fast forward to 2019, when researchers linked three human brains using a brain-to-brain interface (BBI), allowing two participants to transmit instructions directly into a third person’s brain using magnetic stimulation—enabling them to collaborate on a video game without speaking.

Beyond mind control, neurotech has made it possible to simulate pain and pleasure without physical harm. Techniques like Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) and Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs) let researchers manipulate neural activity for medical treatment.

AI is actively working to decode the complexities of the human brain. At Stanford, researchers have used fMRI data to identify distinct “pain signatures,” unique neural patterns that correlate with physical discomfort. This approach could provide a more objective measure of pain levels and potentially reduce reliance on self-reported symptoms, which can be subjective and inconsistent.

Much like Dr. Dawson’s neural implant aimed to bridge the gap between doctor and patient, modern AI researchers are developing ways to interpret and even visualize human thought.

Of course, with all this innovation comes a darker side.

In 2022, Neuralink, Elon Musk’s brain-implant company, came under federal investigation for potential violations of the Animal Welfare Act. Internal documents and employee interviews suggest that Musk’s demand for rapid progress led to botched experiments. As a result, many tests had to be repeated, increasing the number of animal deaths. Since 2018, an estimated 1,500 animals have been killed, including more than 280 sheep, pigs, and monkeys.

While no brain implant has caused a real-life murder addiction, electrical stimulation can alter brain function in unexpected ways. Deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s has been linked to compulsive gambling and impulse control issues, while fMRI research helps uncover how opioid use reshapes the brain’s pleasure pathways. As AI enhances neuroanalysis, the risk of unintended consequences grows.

When Dr. Dawson pushed the limits, and ended up experiencing the death of the patient, his neural implant was rewired in the process, blurring the line between pain and pleasure.

At present, there’s no known way to directly simulate physical death in the sense of replicating the actual biological process of dying without causing real harm.

However, Shaun Gladwell, an Australian artist known for his innovative use of technology in art, has created a virtual reality death simulation. It is on display at the Melbourne Now event in Australia. The experience immerses users in the dying process—from cardiac failure to brain death—offering a glimpse into their final moments. By simulating death in a controlled virtual environment, the project aims to help participants confront their fears of the afterlife and better understand the emotional aspects of mortality.

This episode of Black Mirror reminds us that the quest for understanding the mind might offer enlightenment, but it also carries the risk of unraveling the very fabric of what makes us human.

In the end, the future may not lie in simply experiencing death, but in learning to live with the knowledge that we are always on the cusp of the unknown.

Backseat Driver

In the second part of Black Museum, Rolo recounts his involvement in a controversial experiment. After an accident, Rolo helped Jack transfer his comatose wife Carrie’s consciousness into his brain. This let Carrie feel what Jack felt and communicate with him. In essence, this kept Carrie alive. However, the arrangement caused strain—Jack struggled with the lack of privacy, while Carrie grew frustrated by her lack of control—ultimately putting the saying “’til death do you part” to the test.

The concept of embedding human consciousness into another medium remains the realm of fiction, but neurotechnology is inching closer to mind-machine integration.

In 2016, Ian Burkhart, a 24-year-old quadriplegic patient, made history using the NeuroLife system. A microelectrode chip implanted in Burkhart’s brain allowed him to regain movement through sheer thought. Machine-learning algorithms decoded his brain signals, bypassing his injured spinal cord and transmitting commands to a specialized sleeve on his forearm—stimulating his muscles to control his arm, hand, and fingers. This allowed him to grasp objects and even play Guitar Hero.

Another leap in brain-tech comes from Synchron’s Stentrode, a device that bypasses traditional brain surgery by implanting through blood vessels. In 2021, Philip O’Keefe, living with ALS, became the first person to compose a tweet using only his mind. The message? A simple yet groundbreaking “Hello, World.”

Imagine being able to say what’s on your mind—without saying a word. That’s exactly what Blink-To-Live makes possible. Designed for people with speech impairments, Blink-To-Live tracks eye movements via a phone camera to communicate over 60 commands using four gestures: Left, Right, Up, and Blink. The system translates these gestures into sentences displayed on the screen and read aloud.

Technology is constantly evolving to give people with impairments the tools to live more independently, but relying on it too much can sometimes mean sacrificing privacy, autonomy, or even a sense of human connection.

When Jack met Emily, he was relieved to experience a sense of normalcy again. She was understanding at first, but everything changed when she learned about Carrie—the backseat driver and ex-lover living in Jack’s mind. Emily’s patience wore thin, and she insisted that Carrie be removed. Eventually, Rolo helped Jack find a solution by transferring Carrie’s consciousness into a toy monkey.

Initially, Jack’s son loved the monkey. But over time, the novelty faded. The monkey wasn’t really Carrie. She couldn’t hold real conversations anymore. She couldn’t express her thoughts beyond those two phrases. And therefore, like many toys, it was left forgotten.

This raises an intriguing question: Could consciousness, like Carrie’s, ever be transferred and preserved in an inanimate object?

Dr. Ariel Zeleznikow-Johnston, a neuroscientist at Monash University, has an interesting theory. He believes that if we can fully map the human connectome—the complex network of neural connections—we might one day be able to preserve and even revive consciousness. His book, The Future Loves You, explores whether personal identity could be stored digitally, effectively challenging death itself. While current techniques can preserve brain tissue, the actual resurrection of consciousness remains speculative.

This means that if you want to transfer your loved ones’ consciousness into a toy monkey’s body, you’ll have to wait, but the legal systems are already grappling with these possibilities.

In 2017, the European Parliament debated granting “electronic personhood” to advanced AI, a move that could set a precedent for digital consciousness. Would an uploaded mind have rights? Could it be imprisoned? Deleted? As AI-driven personalities become more lifelike—whether in chatbots, digital clones, or neural interfaces—the debate over their status in society is only just beginning.

At this point, Carrie’s story is purely fictional. But if the line between human, machine, and cute little toy monkeys blurs further, we may need to redefine what it truly means to be alive.

Not Dead but Hardly Alive

In the third and final tale of Black Museum, Rolo Haynes transforms human suffering into a literal sideshow. His latest exhibit? A holographic re-creation of a convicted murderer, trapped in an endless loop of execution for paying visitors to experience.

What starts as a morbid fascination quickly reveals the depths of Rolo’s cruelty—using digital resurrection not for justice, but for profit.

The concept of resurrecting the dead in digital form is not so far-fetch. In 2020, the company StoryFile introduced interactive holograms of deceased individuals, allowing loved ones to engage with digital avatars capable of responding to pre-recorded questions. This technology has been used to preserve the voices of Holocaust survivors, enabling them to share their stories for future generations.

But here’s the question: Who controls a person’s digital afterlife? And where do we draw the line between honoring the dead and commodifying them?

Hollywood has already ventured into the business of resurrecting the dead. After Carrie Fisher’s passing, Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker repurposed unused footage and CGI to keep Princess Leia in the story.

The show must go on, and many fans preferred not to see Carrie Fisher recast. But should production companies have control over an actor’s likeness after they’ve passed?

Celebrities such as Robin Williams took preemptive legal action, restricting the use of his image for 25 years after his death. The line between tribute and exploitation has become increasingly thin. If a deceased person’s digital avatar can act, speak, or even endorse products, who decides what they would have wanted?

In the realm of intimacy, AI-driven experiences are reshaping relationships. Take Cybrothel, a Berlin brothel that markets AI-powered sex dolls capable of learning and adapting to user preferences. As AI entities simulate emotions, personalities, and desires, and as people form deep attachments to digital partners, it will significantly alter our understanding of relationships and consent.

Humans often become slaves to their fetishes, driven by impulses that can lead them to make choices that harm both themselves and others. But what if the others are digital beings?

If digital consciousness can feel pain, can it also demand justice? If so, then Nish’s father wasn’t just a relic on display—he was trapped, suffering, a mind imprisoned in endless agony for the amusement of strangers. She couldn’t let it stand. Playing along until the perfect moment, she turned Rolo’s own twisted technology against him. In freeing her father’s hologram, she made sure Rolo’s cruelty ended with him.

The idea of AI having rights may sound like a distant concern, but real-world controversies suggest otherwise.

In 2021, the documentary Roadrunner used AI to replicate Anthony Bourdain’s voice for quotes he never spoke aloud. Similarly, in 2020, Kanye West gifted Kim Kardashian a hologram of her late father Robert Kardashian. These two notable events sparked backlash over putting words into a deceased person’s mouth.

While society has largely moved beyond public executions, technology is creating new avenues to fulfill human fantasies. AI, deepfake simulations, and VR experiences could bring execution-themed entertainment back in a digital form, forcing us to reconsider the ethics of virtual suffering.

As resurrected personalities and simulated consciousness become more advanced, we will inevitably face the question: Should these digital beings be treated with dignity? If a hologram can beg for mercy, if an AI can express fear, do we have a responsibility to listen?

While the events of Black Museum have not happened yet and may still be a long way off, the first steps toward that reality are already being taken. Advances in AI, neural mapping, and digital consciousness hint at a future where identities can be preserved, replicated, or even exploited beyond death.

Perhaps that’s the real warning of Black Museum: even when the human body perishes, reducing the mind to data does not make it free. And if we are not careful, the future may remember us not for our progress, but for the prisons we built—displayed like artifacts in a museum.

Join my YouTube community for insights on writing, the creative process, and the endurance needed to tackle big projects. Subscribe Now!

For more writing ideas and original stories, please sign up for my mailing list. You won’t receive emails from me often, but when you do, they’ll only include my proudest works.